08/29/21 - The Esotericism of Digimon World

And a few tangents on Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild.

Playing a lot of Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild got me thinking about another game that aspired to the ambitions of an open world experience: Digimon World, for the PS1. Released in 1999, Digimon World was an anomaly among other games in the market, and would go on to become a cult classic, loved (and I use the word “loved” very loosely here) for its foibles, weird mechanics, overwhelmingly open world, punishing difficulty, and charm. I played it as a kid, and again in my 20s on an emulator. I wanna talk about this game because people don’t talk about it enough. Somebody should put it in a museum.

Content warning, I guess: this post mentions poop a lot??? Bear with me.

The game begins with you getting isekai’d into the Digital World, in a place called File City, which looks more like a little-ass hamlet when you first find it. Jijimon, a village elder-type figure who saddles you with some vague “chosen one” rationalizations for your being here, informs you that Digimon around the continent have grown feral due to evil forces. It’s up to you, and your Digimon partner, to gather them to File City and essentially rebuild a functional society. You start with Agumon and Gabumon, the blueprints for Hinata and Kageyama, but we can table that conversation for another time.

Conventional game design tells us that a game should ease you in with a tutorial. Digimon World is a game that throws you into the deep end and tells you that other games did swimming all wrong. Left to your own Digivices, you’re hoisted with the responsibility of caring not for a combat-viable monster, but a child trying to communicate its needs. There’s a gym here… how do I use the gym? Why is training run like slot machines? Who do I fight first? Why does my partner need to poop?? Where’s the bathroom??? Structurally, Digimon World deviates from what you’d expect from other monster collector games with a slew of logistical challenges. Progression through the story is extremely non-linear, and general gameplay is characterized by a pervading sense of what-the-fuck-ness. You have to figure that shit out on your own.

For one thing, the evolution system was extremely esoteric and volatile—the game made little effort to educate you on what factored into evolution, like weight, mood, and highly specific stat thresholds. Evolution is the main draw for a lot of monster games, and the Digimon franchise made the decision very early on with its games to make the most appealing aspect of its universe—turning your “beach balls and jellyfish” into “cars and leather daddies”—the most difficult to understand. Anybody who’s played this game before knows that your partner is most likely going to Digivolve into Numemon, a green slug-like creature with a knack for coprophagia. Next thing you know, your life mission becomes figuring out how you can turn your monster buddy into anything but that.

Improving stats hinged on an entrancingly mundane training system. Running laps, pushing a boulder, and meditating under a waterfall was how you pumped your numbers up, instead of actual battling and a cut-and-dried level-up system. That mechanic probably got me indirectly into Monster Rancher, and how those games did things.

Combat mechanics were clunky and felt like gambling. You had to input a command with a bunch of button mashes and just hope the action comes through, which I guess is how the game went about articulating the concepts of obedience and trust. (This also applies to Monster Rancher!) It wasn’t turn-based, but describing the combat as “real-time” isn’t quite right, when battling doesn’t give a shit about dexterity and reflexes. I imagine it was hard for players to exploit this game for bugs, when the whole game felt like a bug. That’s Digimon for you.

Y’know what you did have, though? A meat farm.

I think what Digimon World tried to do was take the most novel, defining aspects of the Tamagotchi pet-keeping experience—feeding, bonding, growth, waste management—and apply them to a large scale, occasionally hostile environment, where every action and encounter has consequence. Exploring the game’s map mirrored the process of caring for your Digimon partner—your child is a nuanced world, and the world is a petulant child. Both need patience. Both feel like they need a third eye.

This is how I tried to play the game when I was 8 or 9, and I got my DigiDestined ass constantly handed to me by capricious RNG, a glaring lack of basic tutorials, and being too far away from the bathroom. When I tried to play the game again in adulthood, I had hella GameFAQs pages open, detailing specific evolution requirements, quest walkthroughs, day and night cycle quirks, and tricks for avoiding evolving into Numemon at all costs. Old GameFAQs pages are like the internet’s stone tablets, ancient relics that deciphered the mythologies of their time. It’s nearly impossible to complete this game without cheating in some way.

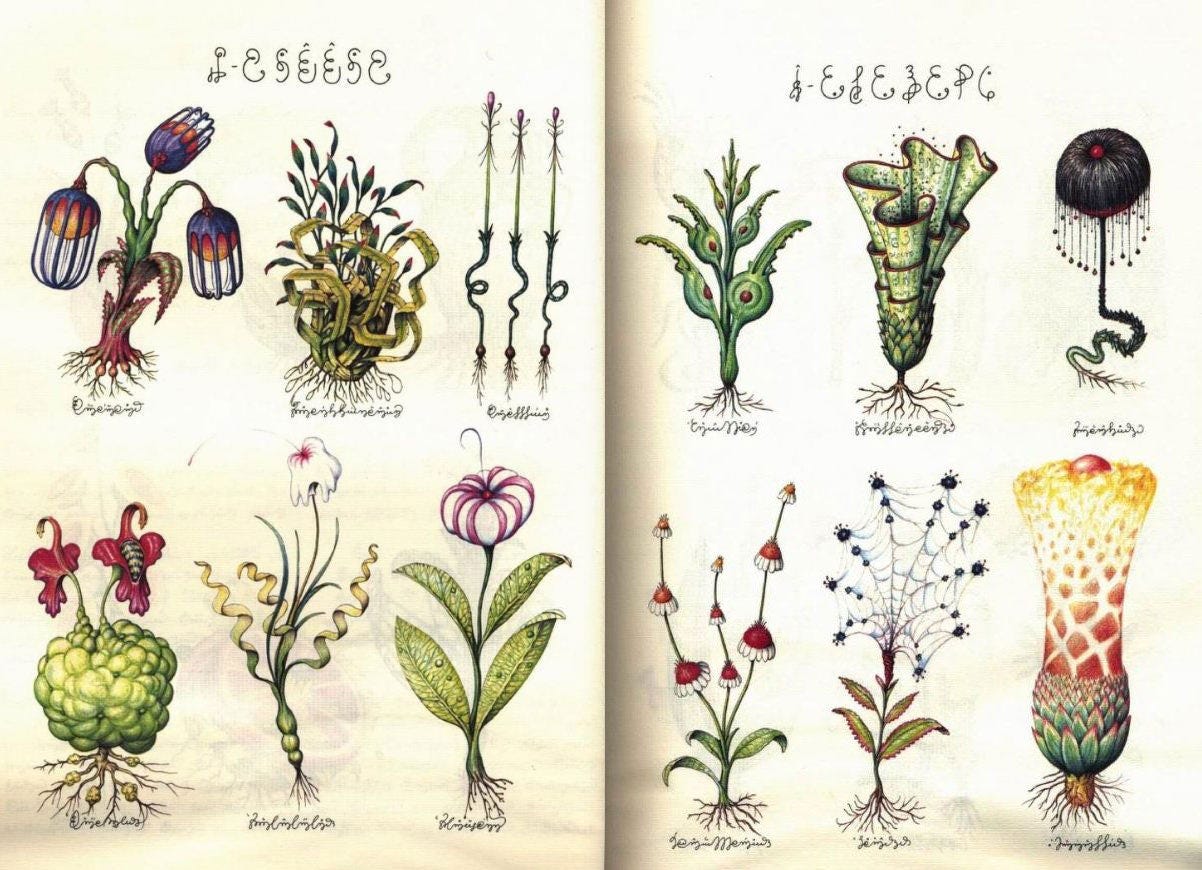

It’s been over 20 years since Digimon World’s release, and the game’s mechanics continue to intrigue and mystify me. It was just so fucking weird. Digimon World reminds me of a book called the Codex Seraphinianus, an encyclopedia of fantastical flora, fauna and phenomena, written in an (allegedly indecipherable) imaginary language by Italian artist Luigi Serafini. I read somewhere that Serafini intended the codex to make you feel the way a child feels reading a book for the first time. Flip through the book and what you’ll experience primarily is bewilderment, the feeling that you’re enjoying yourself because you don’t really understand what’s happening, even though it feels like you do. Digimon World is the Codex Seraphinianus of games.

Can we talk about Breath of the Wild parallelisms real quick? Both games score your exploration of their worlds with almost nothing but the sounds of your footsteps. The scoring is sparse and some of the most pronounced sounds come from you just opening and closing menus. You could travel day and night without coalescing at a resting place if you tried hard enough. It was entirely possible to encounter enemy threats way beyond your level (Digimon World was more unforgiving with its scaling). Lushly rendered environments make up a big part of your aesthetic experience of both games. Personally, I think Digimon World did grainy pixels and blocky polygons better than most games of its time—the graphics felt almost impressionistic. And in Digimon World, your primary quest is essentially putting together Tarrey Town. As you progress through the game, recruiting (read: defeating) different Digimon into contributing their unique services to File City, the more comforts you’re able to avail of in terms of food, money, medicine, and travel. This game makes you fight tooth and nail for quality of life. It’s also kinda wild that you were basically making an autonomous collective.

The look of Digimon World was also very much in a league of its own, and the more it ages, the more the game feels like a memory that isn’t real. The way the land transitions from grass to circuit board, the way floppy disks were just a visual signifier everybody understood at the time, the way pixels were just so unapologetically square—again, this game belongs in a museum.

I did eventually complete the game, with like a Skull Greymon or something? Working around the game’s esoteric mechanics, I’ve found, could be done by simply brute-forcing through them by stockpiling on money and healing and stat-boosting items. At that point the game just felt like a math problem, a thing to be done with. But the game was at its best when it was mysterious and confusing and difficult. No other game in the franchise tops it, save perhaps for Digimon Digital Card Battle haha hot damn that game was fun

Hi! Thanks for reading. Before this newsletter’s list of recommended media, I’m hoping I can get your opinion on a few things.

1) I’m thinking of turning this blog into something I can earn from by using a platform like Ko-fi. For better or worse, I’ve resigned to the idea that writing is how I’m going to be putting food on the table for the rest of my life, and I’m interested in making this blog sustainable. Would you be willing to pay for writing that goes beyond the scope of random hooha I talk about every other week?

2) If so, what kind of content would you like to see this blog put out? What kind of topics would you like me to cover? I’m thinking of bringing back my old column from Young STAR about vintage memes (you deserve it, they don’t), doing some more music writing, and even covering Dungeons & Dragons-related content. Comment below, or message me personally if we’re mutuals!

Felt, an album by composer Nils Frahm. The record is full of gentle, delicate piano textures and flourishes. It’s good sonic wallpaper, and also good to be entirely alone with.

I recently purchased an ebook called Witch + Craft, a Dungeons & Dragons 5E supplement that aims give player characters hobbies and craft specializations. Imagine being a Fighter-Carpenter, a Cleric-Chef, or a Wizard-Glassblower! I went through a bit of it last night, and the book has beautiful art and interesting mechanics that can serve to give your campaign a ~*~slice of life~*~ feel. I’m hoping to apply these mechanics to a future campaign with friends. If you play Dungeons & Dragons and are looking to put more hobby in your hobby, consider buying this book!

This piece called “Critical Attrition: What’s the matter with book reviews?” and Gawker’s snappy counterargument piece entitled “The Intellectuals Are Having A Situation.”

Another one from The Atlantic. The Coronavirus Is Here Forever. This Is How We Live With It.

David Graeber: After the Pandemic, We Can’t Go Back to Sleep

Another one from Gawker: Let People Enjoy This Essay

JRR Tolkien Invented the Term “Eucatastrophe.” What Does It Mean?

Two helpful guides on how to identify “greenwashing.” One from Green & Thistle and another from Ethical Consumer.