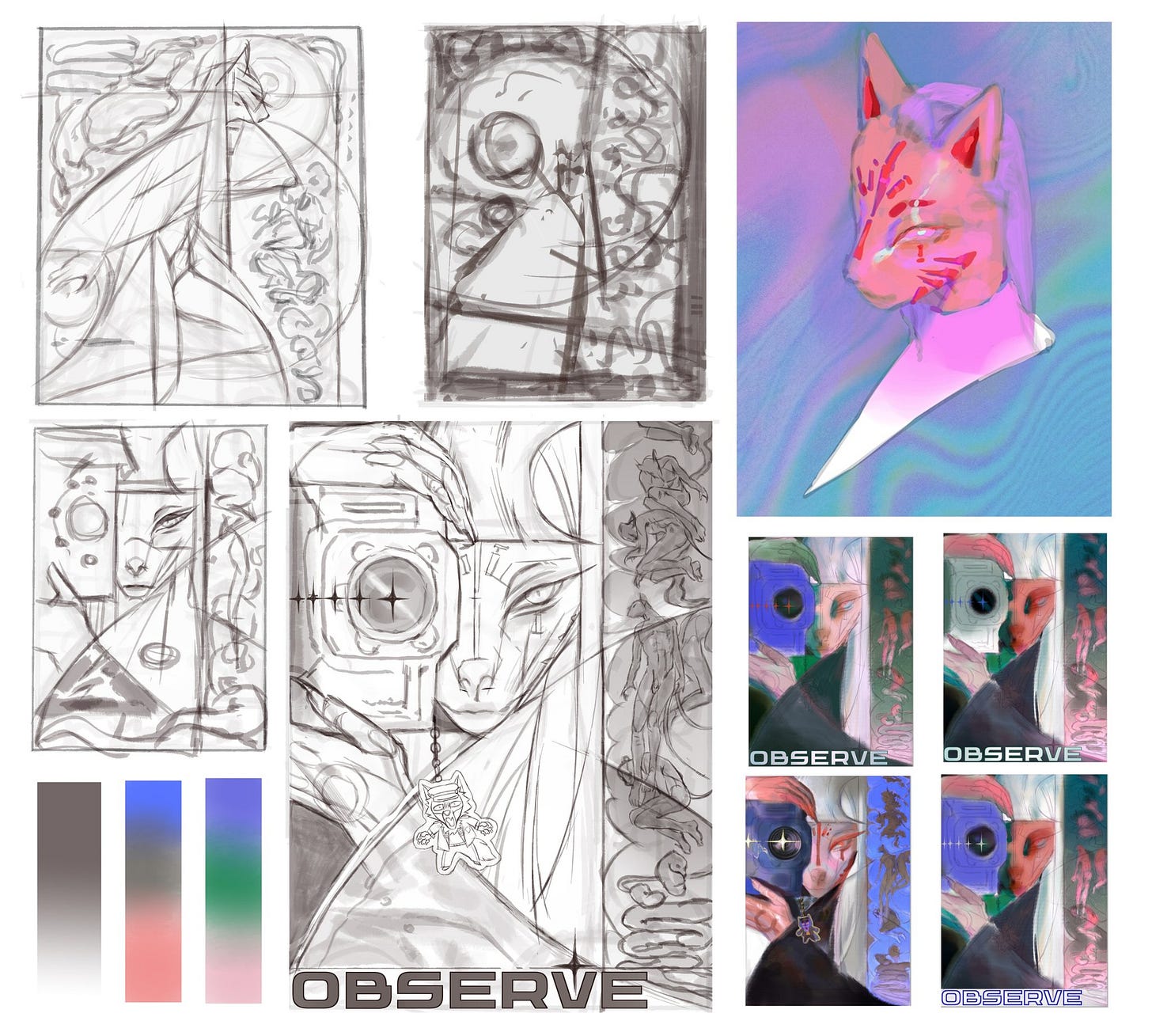

08/05/24 - What aesthetic is this?

"The riches remain dumb unless we have an engaged relationship with them."

Hello! Earlier this year, I was invited to be part of a music journalism panel for MusiKatip. It was me and Jason Caballa and Aldus Santos, and it was pretty awesome. For the brief time I was under the impression that I’d be giving a presentation (instead of it being a live roundtable thing), I prepared this. I’ve made some changes since the first April draft. I hope you like it.

Depending on which side of the algorithm you piss the day away on, “What aesthetic is this?” is a question that populates the comment sections of so many TikToks. I know it’s like that for me. It could be an interesting edit, a slideshow, a piece of graphic design, or a kooky mashup. Example below.

I will give you, right now, a reliable source for finding out the names of aesthetics. There is the website of the Consumer Aesthetics Research Institute, run by a collective of researchers and designers, who define a consumer aesthetic as “a visual movement unified by overarching attitudes and themes that survived long enough or became popular enough to be appropriated by capital (a bar that is being lowered constantly as our cycles of cultural propagation accelerate).” There is also the less “official” but I think equally helpful aesthetics wiki, Aesthetics dot fandom dot com. In their “Aesthetics 101” page, they state:

The word "aesthetic" originated as the philosophical discussion about what beauty is, how we should approach it, and why it exists. Later, the academic field of art history used aesthetic to refer to a set of principles motivating artists and certain periods of art history. However, Millennials and Generation Z started using that term as an adjective that describes what they personally consider beautiful. For example: "After Denise finished watching The Virgin Suicides, she said, 'Wow. That was so aesthetic.'"

Codification is important. And it’s always something with us, to jump at the chance to name a thing.

“What aesthetic is this?” is an inoffensive question. When someone asks what the “aesthetic” of a thing is, they do so in the interest of looking for things similar to it by way of genre, style, or affect, satisfying appetite while honing taste. Frutiger Aero. Global Village Coffee House. Digicore.

It’s weird though because while we’ve always embarked on our search for new media with these motivations, it is, to my mind, a recent development for people to phrase the question in this way. Give me the name of this aesthetic, and I will input the relevant search terms into a search engine. The phraseology of “That’s so aesthetic” also implies that “What aesthetic is this?” is the clarion call of the modern media consumer, who navigates a cultural landscape that is both hyperabundant and flattened.

What aesthetic is this?

In the mid 2010’s–so roughly a decade ago (I was in college)–I and the rest of my generation witnessed firsthand the rise of what the press called “the bedroom musician.” BuwanBuwan Collective was getting its start while Logiclub was positioning itself as a prime mover. At this time, I was writing for the school newspaper and interning at Young STAR. And I distinctly remember a certain word that just kept popping up everywhere I turned. Vibes. Vibes vibes vibes. Jess Connelly. Chill vibes. Outerhope. Ambient vibes. Here a vibe, there a vibe, everywhere a vibe. I’m surprised the word “vibe” didn’t snap under the sheer weight of every John, Jane, Enzo and Bea using “vibe” like a crutch. How easy it was to read this glaring deficiency, that these people just didn’t know what a delay pedal was, how much weight the word “hypnagogic” can carry. It’s like describing a Telecaster’s guitar sound as “twangy.” Well of course it’s twangy. It twangs.

What aesthetic is this?

I was a big metalhead in high school. I don’t know how it is now, but the way it was back then was that you had to be puritanical about shit for no reason. Are they really black metal if they didn’t burn a church and kill their friend in the forest, frostbitten and sunken-eyed in the Scandinavian cold?

Nobody told us to do this. None of us received a memo from the high council of steel to subscribe to genre puritanism. Looking back, there was also something very Idk… white supremacy adjacent to this idea that we, in this insulated community of self-marginalizing nerds, shouldn’t cross-breed our tastes with other genres. Idk. There’s something mildly sinister to “What aesthetic is this,” and that’s when we use it to put our taste on pedestals while branding other styles as inherently degenerate or inferior. It’s corny when people do that to pop. It’s lame when people do that to rap. For a while it was rather fashionable to rag on country, and hey, a couple Mitski, Beyoncé, Miley Cyrus and Kacey Musgraves and Waxahatchee records later, we’re switching out our Doc Martens with actual boots made for walkin’.

What aesthetic is this?

There are only so many ways Spotify can recommend new music according to your listening habits, and lately they’ve been getting a little spicy with it. Like, they’ll give you a playlist named ALLURE with a subhead that goes “For the baddies.” They’re doing that thing now where they make what they call a “day list” for you, which is, to my understanding, a procedurally generated playlist that supposedly plays to your tastes and harps young people language. What is an EMPOWERING HOT GIRL WALK TUESDAY EVENING?

Consider as well Johan Rohr, the Swedish composer behind 650 dupe artist profiles that have marauded Spotify’s mood playlists, racking up over 15 billion plays for more than 2,700 songs, which are owed to the likes of “Minik Knudsen,” “Csizmazia Etel,” and other common cuckoo aliases kicking chicks out of their nests. Sabrina Carpenter’s “Espresso” barely scratches the surface regarding who’s rigged to get what when a passive listener lets an algorithm masturbatorily rummage through its banks. The play numbers and red herring profiles suggest an elaborate scheme by CEO Daniel Ek to plonk Rohr into playlists as a literal industry plant, an artificial means of inflating the data to mendaciously prop Spotify up as the artist-first app it purports itself to be. The Swedes, at it again!

Barring any analyses or direct condemnations of an app I don’t expect anybody to delete from their phones, it’s a little fucked, right? That we’re not sideboard-surfing anymore?

What aesthetic is this?

What was the name of that guy who made “A CHILL MIX” playlists on his Spotify and was exposed for making multiple similarly-titled playlists for a bunch of other girls? Crazy. A turning point. A Twitter main character.

What aesthetic is this?

“Music is everywhere. It has gained on us as our waking life turns into one long broadcast, for better and for worse—often for worse. But we have gained on it, too, learning how and when we want to absorb it. The unit of the album means increasingly little to us […] Other sophisticated music-data algorithms, such as those created for Spotify and other clients by music-data companies like the Echo Nest, profile your taste in music as a condition related to who you are in general—where you live, how old you are, how you are likely to vote. With these advances we can essentially be fed our favorite meal repeatedly. We develop a relationship of trust with—what? Whom? A team of programmers? Our own tastes, whatever that means, translated into a data profile?

This all sounds very bad. It probably is very bad. Infinite access, unused or misused, can lead to an atrophy of the desire to seek out new songs ourselves, and a hardening of taste, such that all you want to do is confirm what you already know. But there is possibly something very good, too, about the constant broadcast and the powers of the shuffle and recommendation effects. There is a possibility that hearing so much music without specifically asking for it develops in the listener a fresh kind of aural perception, an ability to size up a song and contextualize it in a new or personal way, rather than immediately rejecting it based on an external idea of genre or style. It’s what happens in the moment of contextualization that matters: what you can connect it to, how you make it relate to what you know.”

“In many cases, having rapidly acquired a new kind of listening brain—a brain with unlimited access—we dig very deeply and very narrowly, creating bottomless comfort zones in what we have decided we like and trust. Or we shut down, threatened by the endless choice. The riches remain dumb unless we have an engaged relationship with them. Algorithms are listening to us. At the very least we should try to listen better than we are being listened to.”

—Excerpt From: Ben Ratliff. “Every Song Ever”

What aesthetic is this?

If I’m interviewing an artist, I don’t ask the question directly. It’s rude, y’know? You need to phrase it differently. Who are your influences? What was the inspiration behind this record? Get to know their contemporaries, augur the patterns, listen. Codifying who you are according to a genre lexicon isn’t the prison sentence people say it is—in fact it’s rather freeing. It is a means for the artist to anchor themselves to a particular lineage, a way to make visible the giants whose shoulders we stand on. Don’t get caught acting the fool when the ground shakes and you don’t know what’s going on.

What aesthetic is this?

University Challenge is the name of a game show hosted by news presenter Amol Rajan and broadcast on the BBC network. A snippet of one of the show’s episodes went viral some time ago among vinyl heads and dance music sages. Amol Rajan asks: “What name is given to the genre of dance music that developed in the UK in the early 1990s out of the rave scene and reggae sound system culture, associated with acts such as A Guy Called Gerald and Goldie?” One of the students hazards an intelligent guess: “Drum n’ bass?” It’s a fair guess. Rajan however responds with “I can’t accept drum n’ bass. We need jungle, I’m afraid.”

Just like that, God tosses a golden soundbite from the Garden of Hesperides, and DJ’s swarm to sample and graft. One can imagine what kind of revelry ensues if like, say, you’re at the club, speakers booming, then you hear, “I can’t accept drum n’ bass, we need jungle I’m afraid,” followed by a rockslide of sped-up amen breaks. Asking for the aesthetic, then identifying it, poses an invitation to create. Create or die. Listen or die. What aesthetic is this?